Published on Livewire 20/10/2022 (Original Article Here) – Romano Sala Tenna

Firstly, this piece falls into the ‘this seems impossible’ category. Just warning you before you dismiss the data or start throwing insults at the author.

Secondly, this piece does not advocate a buy-and-hold strategy. Surprising when you read the first part; but if you read it to the end, it will become clear. Whilst BT’s slogan ‘It’s time in the markets not timing the markets’ was clever and catchy, it is only partially valid in our view.

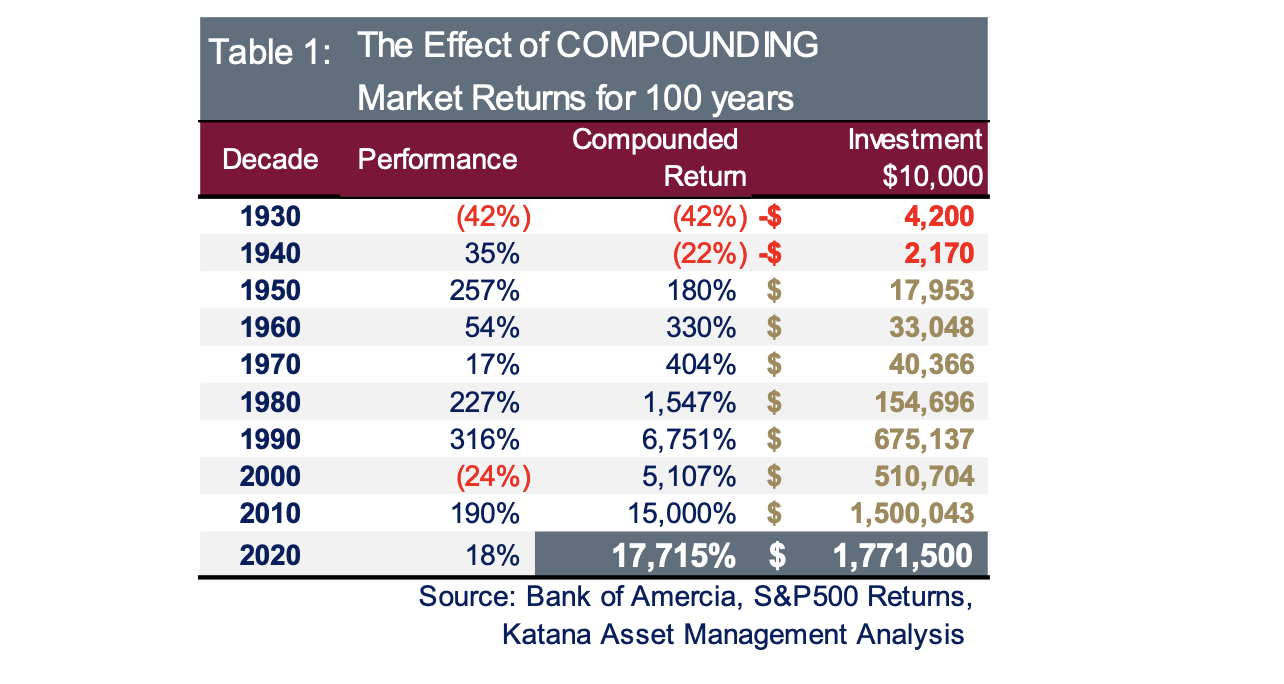

So, to the data. CNBC picked up a piece authored by Bank of America which compiled the returns for the S&P 500 for each decade from 1930 until 2020. The returns highlight Katana’s #1 favourite investing principle: the power of compounding.

Time in the market

Despite an innocuous start (-42% for the decade closing out 1930), we have witnessed some remarkable returns. During the 1940s the market rose by 257%. In the 1970s it jumped 227% and more recently in the naughties, it was up 190%. But what is truly astounding, is the impact of compounding. Over the journey, earning returns on past returns has generated an extraordinary result.

By compounding performance for 100 years, the impact is an astounding 17,715% return or 177% p.a. This means $10,000 invested 100 hundred years ago, would be worth in excess of $1.77m today.

Even when allowing for inflation, this total is startling.

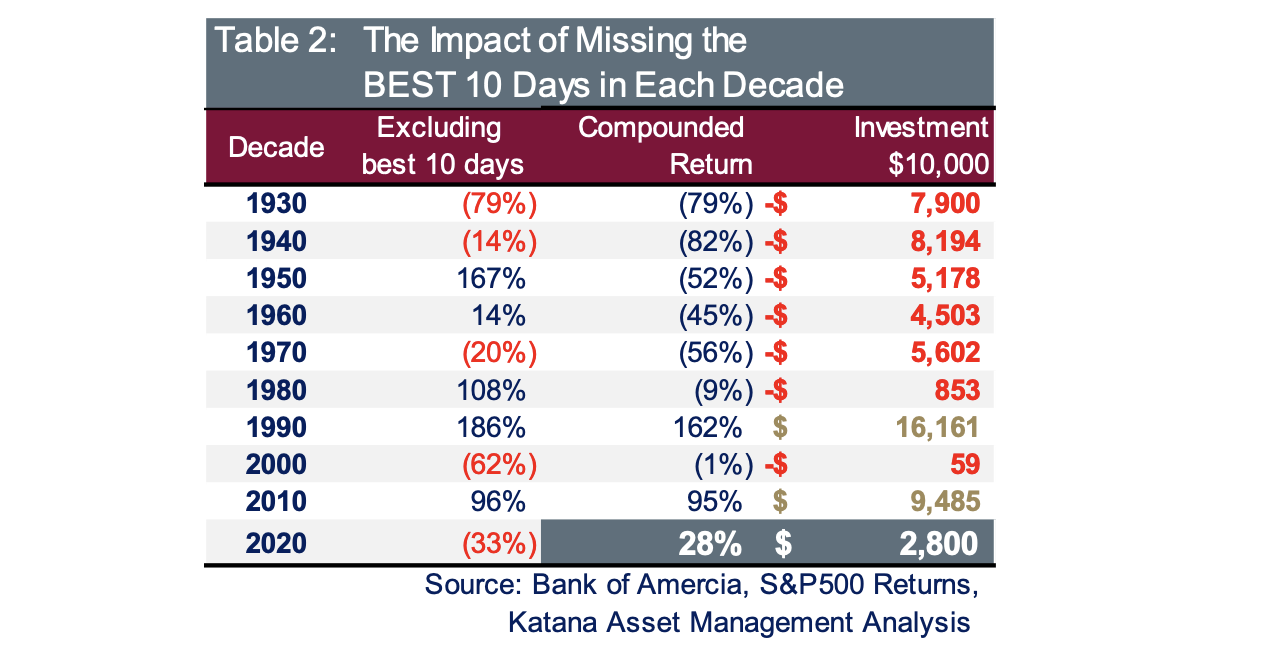

Now, where does the 100 days come in? Let’s imagine that in your efforts to time the markets, you missed out on the best 10 days of returns each decade (so 100 days over the century). What impact would this have?

Rather incredibly, missing just 100 days would mean the difference between a return in excess of $1.77m and…$2,800!

Yes, that is the correct number of zeroes. Missing the best 100 days would mean a total return of just 28% (for 100 years) versus 17,715%. The difference between inter-generational wealth and abject poverty.

Timing the market

So right about now, all the naysayers who voraciously speak against any efforts to time markets are popping champagne corks and high-fiving each other. Those who sit in this camp may wish to discontinue reading at this point.

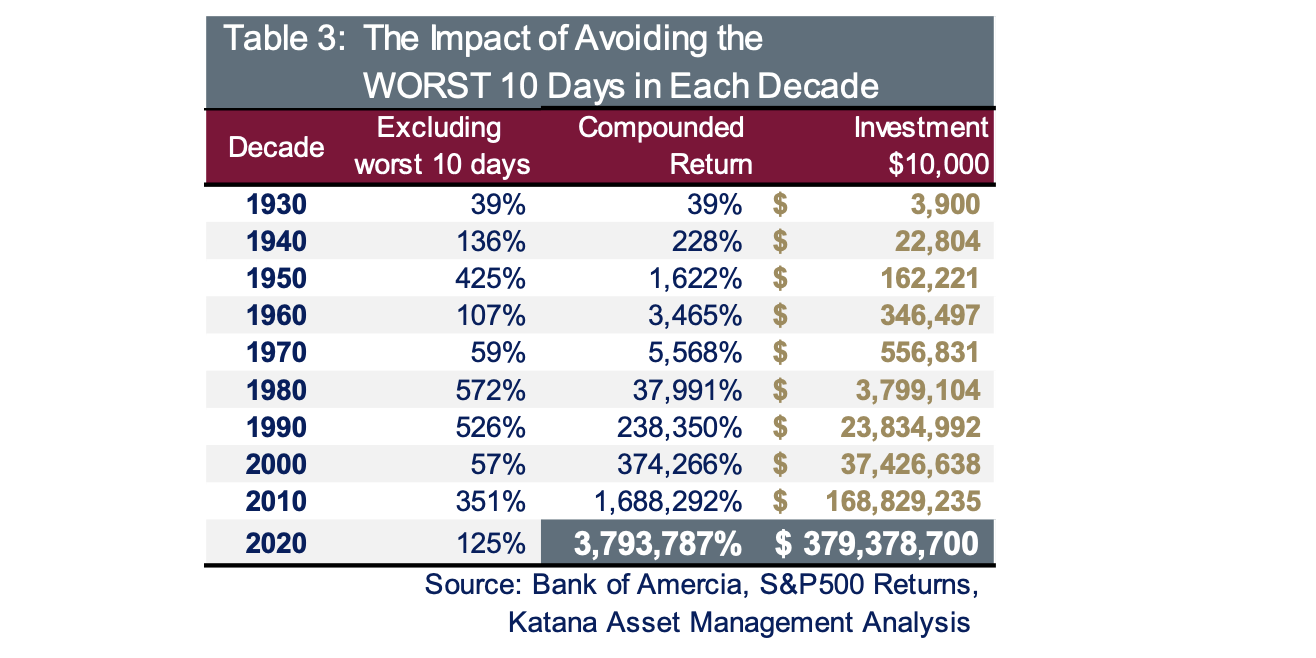

For balance, let’s now take the opposite view, and consider the impact on total returns of successfully timing markets. Let’s consider the impact of ‘missing out’ on the worst 100 days in the past century. The results are even more incredulous than one would think possible. If an investor was somehow able to avoid the worst 100 days in the past century, the total return would be a staggering 3,793,787%. $10,000 would have compounded to in excess of $379 million.

Of course, it is just short of statistically impossible to avoid the 100 worst days. But what this time study clearly demonstrates, is that even just missing one or two of the worst days each decade would have an enormous effect on returns. An effect so astounding, that it would justify the risk of missing some of the best days.

And whilst not included in this piece, further analysis of the data also demonstrates that if you miss an equal number of good and bad days, you still end up substantially in front. For example, if you miss the best 100 days and avoid the worst 100 days, the total return over the century would be in excess of 27,000% (versus 17,715%).

What does this mean?

So does this mean that attempting to time the market is actually the better approach?

Everyone’s answer to this question will be different. At Katana, we see some validity in both time in the market and timing the market.

Firstly, time in the market. There can be no argument that turning $10,000 into $1.77m by doing nothing is an incredible result. By any metric. Time in the market is a proven strategy. In our view, this should be the default position. The default position for inexperienced investors full stop. And the default position for experienced investors in the absence of a clear case to the contrary.

However, there can also be little doubt from this data, that timing has a place. Even applying a simple risk-return analysis, confirms the merit of attempting to eliminate some bad days. Avoiding one or 2 of the worst days each decade would have a pronounced impact on returns in the vicinity of many 10,000’s of % when compounded over time.

Of course, the main argument against attempting to time the market is that it is near on impossible to do or that you equally run the risk of missing good days. This is where Katana’s viewpoint differs. Yes attempting to eliminate every bad day or capture every good day is impossible. But the data clearly indicates that to meaningly outperform, this is not required. We simply need to miss a handful of bad days each decade to change the course of our wealth. And if your timing was such that you miss an equal number of good and bad days, you still end up substantially in front.

Therefore…

The default position is to be invested in the market. Where there is an elevated level of risk that is not already the consensus position – history would support making an active call around weightings. But don’t jump at shadows – timing the market should be the exception rather than the norm.